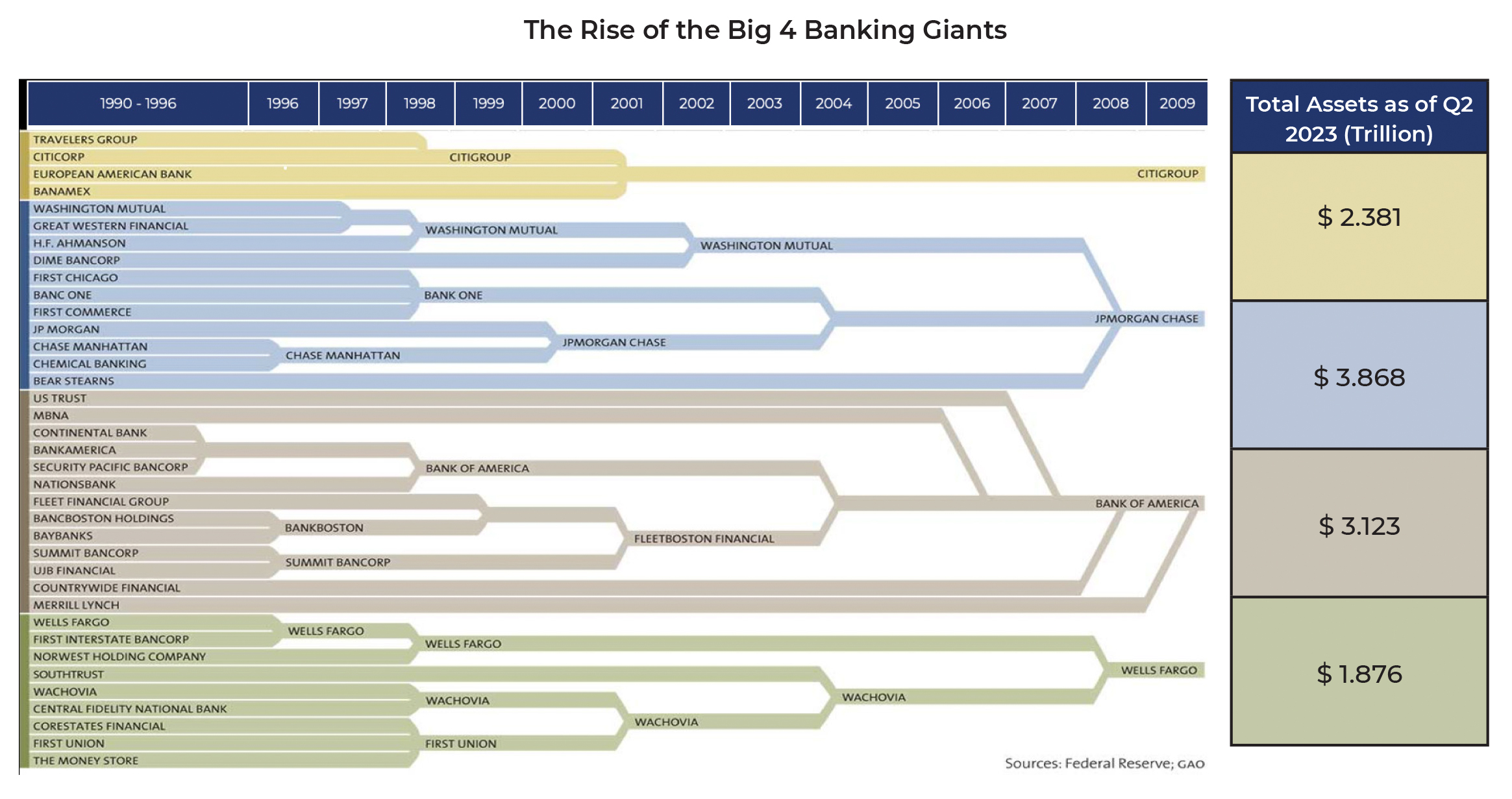

Mergers and acquisitions (M&A) have played a significant role in the banking industry over the last four decades. The U.S. banking industry in particular has witnessed more than 16,000 mergers over the last 40 years. That’s an average of 400 bank mergers annually, a consolidation ultimately resulting in the Big 4 U.S. banks owning over 40% of the industry’s assets.

Amid ongoing M&A activity, this article will delve into the planning and implementation of post-acquisition integration projects. But first, it is worth taking a step back to understand the various laws and regulations that have shaped U.S. banking M&A over the last century.

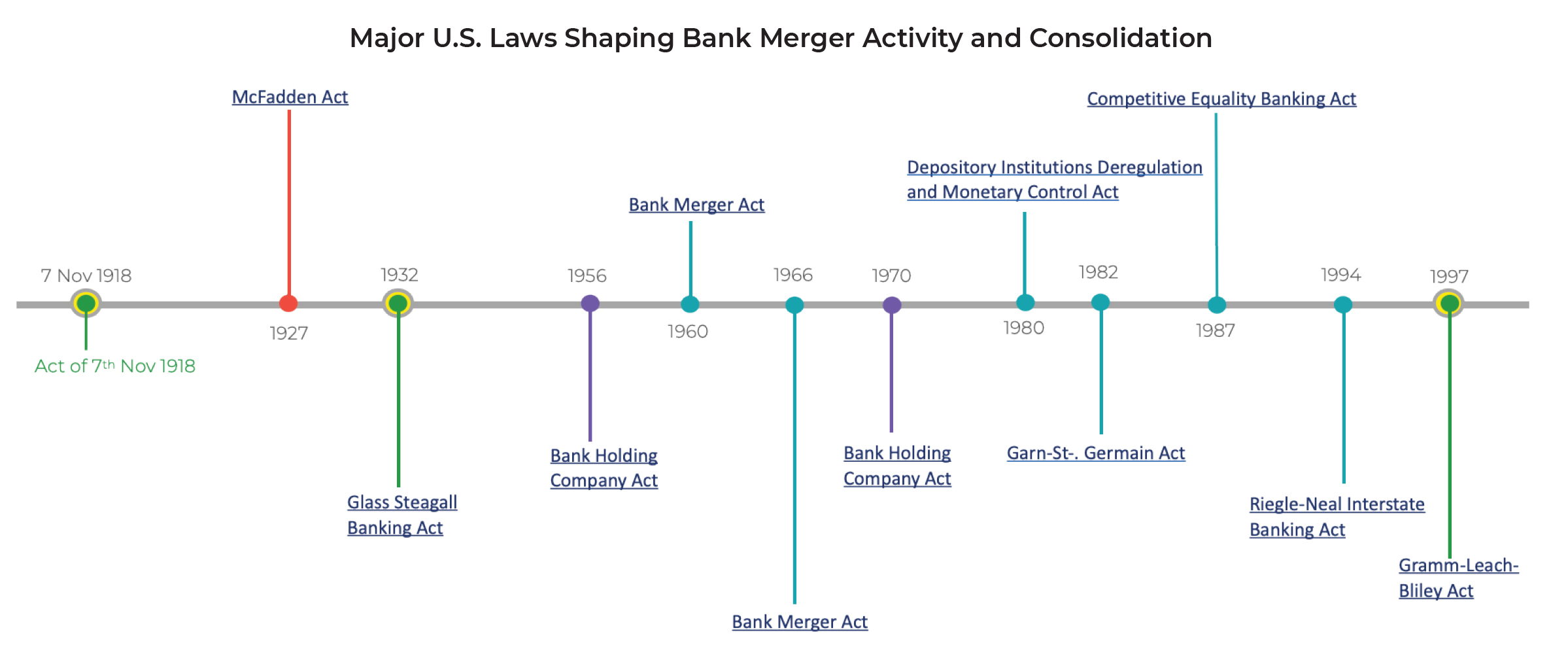

The early 1900s witnessed bank mergers occurring at the rate of 150 to 300 per year following an act in November 1918 that allowed the merger of two national banks located in the same county or city. This subsequently led to the passage of the McFadden Act, which enabled both state and national banks within the same county or city to merge, resulting in the formation of branch offices.

Fast-forward to the enactment of the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act (1980) and Garn-St. Germain Depository Institutions Act (1982), after which the industry experienced regional consolidation fueled by both intrastate and interstate bank mergers.

The 1990s ushered in a flurry of bank merger activities (almost double the speed of activity in the ‘80s) as the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act broke the barriers between an investment bank and commercial bank. This law sowed the seeds of massive expansion—i.e., grow big or go out of business!

The decade of consolidation in the ‘90s continued into the first decade of the 2000s, albeit at a slower pace, leading up to the reshaping of the banking landscape due to global financial crisis of 2007-2008. The passage of the Dodd-Frank Act and Emergency Economic Stabilization Act in 2008 resulted in structural changes in the banking industry coupled with the genesis of Big 4 banking giants. With the financial crisis, the U.S. banking industry witnessed over 3,000 bank mergers during the first 10 years of 2000.

The second decade of 2000s brought a slightly slower pace with around 2,400 bank mergers, or an average of approximately 240 each year between 2010 and 2020.

The current decade is experiencing disruptive macroeconomic and geopolitical forces that are reshaping the banking industry landscape owing to a multitude of factors, such as higher interest rates, the finalization of Basel III global capital rules, geopolitical tensions, and decarbonization and an emphasis on climate change. Additionally, the exponential growth of new technologies such as generative AI, embedded finance, open data, and the digitization of money will continue incentivizing bank M&A both within and outside national borders in the years to come as banks adapt to new competitive dynamics.

Post-Merger / Acquisition Integration Considerations

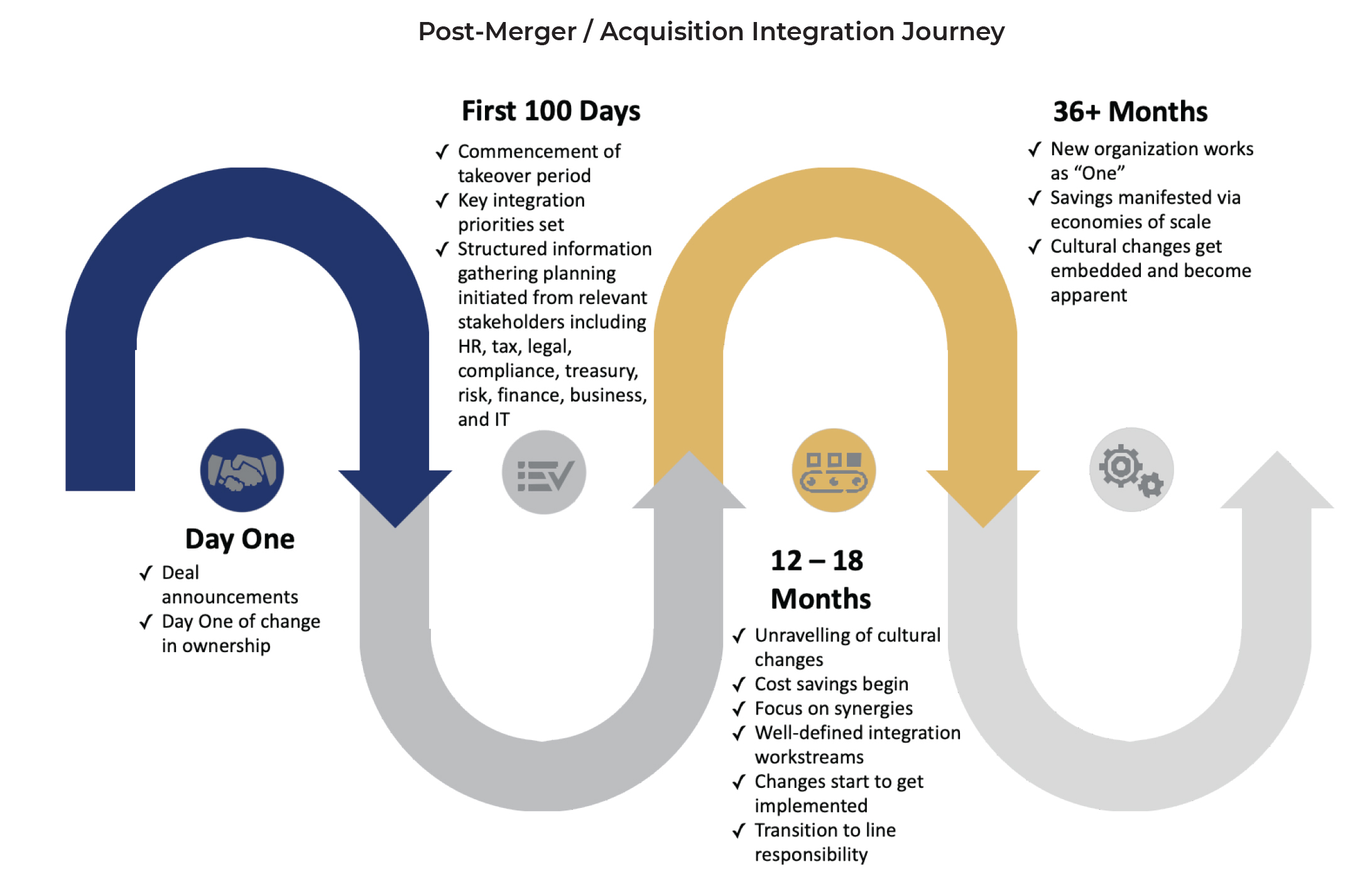

Since the banking industry is likely to witness further waves of M&A, it is important to understand the underlying dynamics of executing a post-merger / acquisition integration project.

Post-Merger/Acquisition Integration – Day-1 Readiness Considerations |

|

| Initial Steps | Prior to initiating the post-merger / acquisition integration, build an inventory of any potential changes to:

|

| Communication |

|

| Governance Changes |

|

| Infrastructure Gap Analysis |

|

| HR Information | Determine employment law implications of entity consolidation, liquidation by analyzing the:

|

| Client Onboarding / Know Your Customer |

|

| Operational Process |

|

| Contract Portfolio |

|

For any large post-acquisition integration project to be successful, it is important to identify the overriding strategy and business objectives early in the global integration process and ensure that these objectives are prioritized and supported by the management. While a typical integration plan gets executed over a long period of time, stretching anywhere from two to three years, a successful integration program needs to identify quick wins eliminating the non-core legal entities. The hypothesis defining the overriding business strategy and objectives needs to be tested and challenged in order to derive the quick wins in eliminating / liquidating the non-core entities.

Business Objective – Challenge / Decision Criteria |

||

| Key Decision Criteria | Yes / No | Comments |

| Does the legal entity (LE) target solution reduce the bank’s operating costs? | ||

| Does the LE target solution support the business strategy at minimal cost? | ||

| Are there any constraints on moving assets, entities, and people? | ||

| Is this the minimum number of LEs permitted by the jurisdictional regulator/s in order to conduct planned business? | ||

| Is all non-regulated activity delivered outside regulated LEs? | ||

| Does this LE solution provide an optimal capital and liquidity outcome for the business? | ||

| Does this solution optimize the use of branches and non-regulated entities? | ||

| Does this LE solution de-duplicate supporting infrastructure to the best possible extent? | ||

| Does the solution optimize the bank’s cash tax position, e.g., leveraging double tax agreements or avoiding value-added tax and any product-related taxes (need not be absolute)? | ||

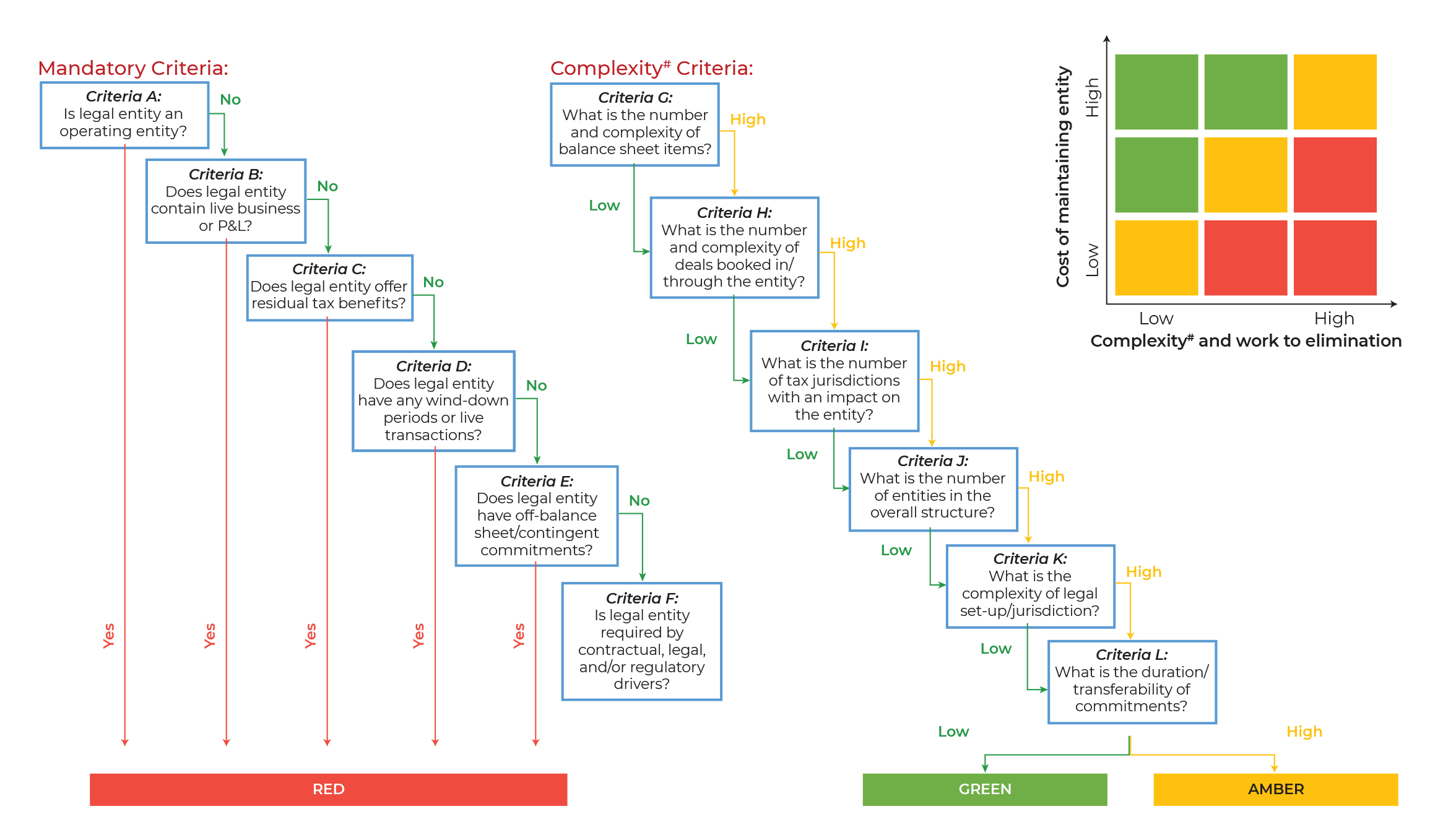

The manner in which the complexity of the non-core LEs is to be assessed depends on the drivers of elimination.

- Green – These entities may be ‘quick wins’ for the project. Common criteria may include solvent entities, no recent activity, intra-group receivable balances only and no cash, no third-party creditors with inter-company liabilities only, no off-balance-sheet issues identified.

- Amber – These entities have elimination blockers requiring further investigation and resolution. Common criteria may include solvent (as above) or insolvent through intra-group payable balances only, no third-party creditors except tax authorities, assets may include cash/cash equivalents or investments in subsidiaries, likely to be non-trading with some potential off-balance-sheet issues identified.

- Red – These companies have significant elimination blockers requiring further investigation and resolution. Common criteria may include off-balance-sheet issues identified such as real estate ownership, intellectual property ownership, contracts, guarantees, warranties, ongoing litigation, employee issues identified including pension scheme association, and likely to be trading entities or have investments in trading entities.

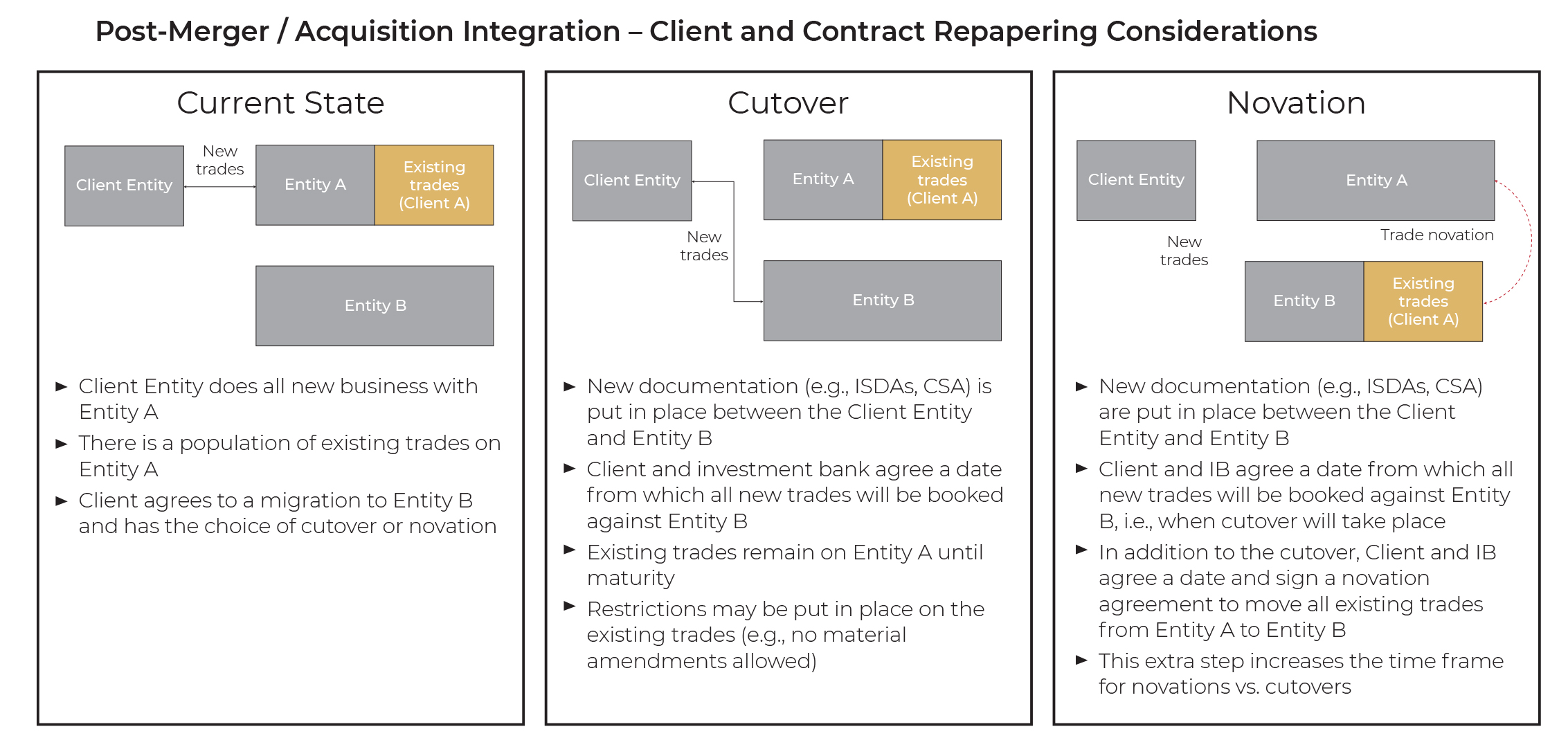

Client Considerations

- Client preference as to migration type needs to be considered.

- If portfolios are complex, the client may not have the operational capacity to agree to a novation and so may only want to book future business onto the receiving entity.

- Similarly, the client may want to have all of their exposure with one single entity to gain netting benefits as so may prefer a novation.

Capital and Credit Risk Impact

- Moving a large portfolio of trades from one entity to another will have an impact on the receiving entity’s capital ratio. The magnitude of this impact will determine whether the business wants to novate such a portfolio over to the receiving entity.

- Where existing positions are left on the current entity, the bank will have exposure to the client on two legal entities. This will have a potentially negative credit impact as positions and collateral cannot be netted across the two entities. This may result in risk management requesting for a novation to take place.

Product Set-Up of Trade Portfolio

- Consider the tenor of trades. If trades are short dated, the business may be happy for these trades to remain on the current entity until maturity. Longer dated positions may be more likely to be in scope for novation.

Time Frame of Migration

- How quickly both the business and the client want the migration to take place will impact whether a cutover or novation is chosen.

- A shorter time frame may result in a cutover choice as opposed to a lengthier novation.

- Where the migration process is being driven by compliance to new regulation, any upcoming regulatory deadlines can dictate time frames.

Post-Merger / Acquisition Integration – Program Risks and Suggested Mitigating Actions

The key to developing and implementing an effective post-acquisition integration plan and overcoming inevitable challenges lies in identifying the key program risks and appropriate mitigation actions. Provided proper and prioritized attention is given by the right people at the right time to the planning and implementation of the integration, the likelihood of achieving a successful integration will be significantly increased.

| Post-Merger / Acquisition Integration Program Dimensions | Post-Merger / Acquisition Integration Project / Program Risk | Mitigating Action |

| Executive Sponsorship | Failure to obtain and communicate executive sponsorship and to set entity eliminations as a top priority across functional and line-of-business (LoB) teams leads to inability to maximize the number of eliminations, objections being raised without appropriate challenge, knowledge professionals inadequately participating in legal entity assessments, etc. | Project “kick-off” is accompanied (and sustained) by appropriate messaging from leadership across all functional and LoB teams:

|

| Business Case | Failure to develop a prudent and manageable initial project scoping, e.g., failure to initially focus on high-cost and/or quick win entities leads to inefficient deployment of resources, inability to secure speed, lost opportunity to anchor post-merger integration as a successful initiative, etc. | Establish the business case as an initial matter, and clearly identify entities with meaningful cost structures that are feasible to eliminate within acceptable time frames. |

| Early SMA Involvement | Failure to allow subject matter advisors (SMAs) early access to integration program stakeholders leads to need to engage stakeholders multiple times to secure relevant information and validate proposed solutions. | Ensure project leaders are aware of the importance in involving the SMAs (both internal and external) in all key assessment interviews so that “engagement of the business” is efficient and effective while interruption to internal teams is minimized. |

| Prioritizing “Objections to Elimination” | Failure to validate proposed solutions with the most complex stakeholders as an initial matter leads to alternate stakeholder groups losing time assessing potential eliminations that are commercially infeasible elsewhere in the business. | Evaluate and rank functional and LoB assessment data by complexity, addressing the toughest objections first so that additional time spent on lower-level objections is reduced or eliminated. |

| Connectivity to Related Workstreams | Failure to connect post-merger / acquisition integration efforts to related strategic initiatives, e.g., governance (population management and risk architectural tiering), living wills, business performance improvement initiatives, etc. leads to need to engage stakeholders multiple times to secure relevant information and loss of ability to capture leverage opportunities between project teams, etc. | Ensure project plan identifies linkage between post-merger / acquisition integration efforts and other strategic initiatives, sets out plans for coordination of efforts, data sharing, etc.

|

| Identifying and Assessing Ripple Effects | Failure to assess “out-of-country” implications, e.g., loss of valuable tax attributes and/or legal protections “down-chain,” incurrence of unexpected tax implications “up-chain,” e.g., controlled foreign company provisions lead to unexpected tax cost and/or legal exposures, which generate unnecessary costs and risks to the organization. | Ensure “up-chain” and “down-chain” out-of-country implications are vetted in order to gain speed to eliminations.

|

| Leveraging Recurring Themes | Failure to identify and document “recurring stakeholder themes” to multiple legal entities to which they relate leads to lost opportunities to deploy solution management across sub-populations of legal entities. | Ensure recurring stakeholder themes are properly identified and associated to the relevant entities so that single solutions can be leveraged across sub-populations of legal entities, speed can be gained, and implementation costs reduced. |

| Contingencies | Failure to protect value: loss of deferred tax assets, crystallization of liabilities (pension scheme deficits); renegotiation of contracts by customers or suppliers.

|

Integration program sponsors should ensure full communication with stakeholders within the business to fully understand the potential impact of entity elimination or business transfer and develop an implementation roadmap that mitigates risk. |

| Transactional Design Architecture | Failure to develop a clear and cross-functionally agreed transactional architecture for the implementation stage reduces opportunities to pattern recurring transaction sets, deploy thoughtful sequencing of assets, lower legal costs, streamline tax return reporting, etc. | Ensure that a design architecture for each jurisdiction and/or LoB is compiled and agreed before effecting eliminations so that the most efficient coordination and sequencing of asset movements is captured. |