The 2008 global financial crisis was triggered by a failure to manage financial risk that wiped out trillions of dollars in value between 2008 and 2009. The next banking crisis could come from a failure to manage so-called conduct risk, unless effective conduct-related governance is put in place to establish better risk and control methods.

Conduct risk can cause detriment, either financial or non-financial, to customers, an organization, the industry, or other stakeholders. Examples include improper trading or the sharing of material non-public information between an employee and a third party. It has also been identified as a key risk attributable to other processes, for example, failures in “know your customer” and client lifecycle management practices.

As 2020 drew to a close, conduct-related governance lapses were seen to have led to enforcement actions at several systemically significant global banks. Billions of dollars in punitive fines have been levied by governments and industry sector regulators for violations arising from various business lines and functions. These include instances of LIBOR manipulation, FX manipulation, and shortcomings in other areas. It is also notable that regulators are more frequently sanctioning individuals.

Banks and other financial services companies tend to address conduct-related risk as an exercise in hindsight. Put another way, misconduct is identified and analyzed only after it has taken place or is discovered to be well underway. However, most regulators have concluded that misconduct follows, in no small measure, from toxic cultures that promote illicit self-dealing and other forms of malfeasance. Increasingly, regulators are turning their supervisory attention to better predicting these issues before they happen.

Controls Fall Short of Regulatory Expectations

Regulators worldwide are now better coordinated and more consistent in their approach to addressing conduct risk. Overall, they have highlighted insufficient progress in conduct risk frameworks and culture programs. Here’s what regulators have come to expect and how banks have been falling short:

- Expected: A comprehensive conduct risk framework embedded throughout the organization that is subject to continuous review, challenge, and improvement.

- Shortfall: Many organizations still have much work to do here.

- Expected: Technology to bring tangible improvements.

- Shortfall: The promise of delivery is too often followed by failure. Big data solutions and surveillance technology continue to generate too many false alerts.

- Expected: Processes in place to monitor emerging and indicative conduct risk.

- Shortfall: Banks stop short at horizon scanning, which is no panacea.

Meanwhile, working from home has presented challenges for employers. Reliance on technology has increased as front office supervision has become more difficult. But information barriers are easily compromised, and the effectiveness of alerts has been called into question.

The Disconnect Between Knowing and Doing the Right Thing

Why do banks still struggle to produce credible and compelling evidence that they have well-managed conduct risk protocols in place?

Banks already invest heavily in predictive technologies that allow them to anticipate behaviors externally—such as tools that forecast market movements—giving them a competitive edge. But when faced with predicting internal behavioral tendencies, they suggest it is impossible to achieve.

Another way to look at it: In many areas of compliance, banks are all well-versed in defining risk appetite statements, developing risk taxonomies, implementing risk frameworks, identifying inherent risks, examining controls, and determining residual risks. There are remediation programs for those instances where the controls are not sufficient and the residual risks are above tolerances defined in a risk appetite.

So, if awareness of conduct risk exists, compliance frameworks are generally well-understood, and regulators pay attention and issue fines, it begs the question: Why does conduct risk still occur with relative frequency?

This disconnect is no longer defendable—there are tools and approaches that allow banks to achieve higher conduct risk identification and mitigation standards.

Snapshot of the Conduct Risk Landscape

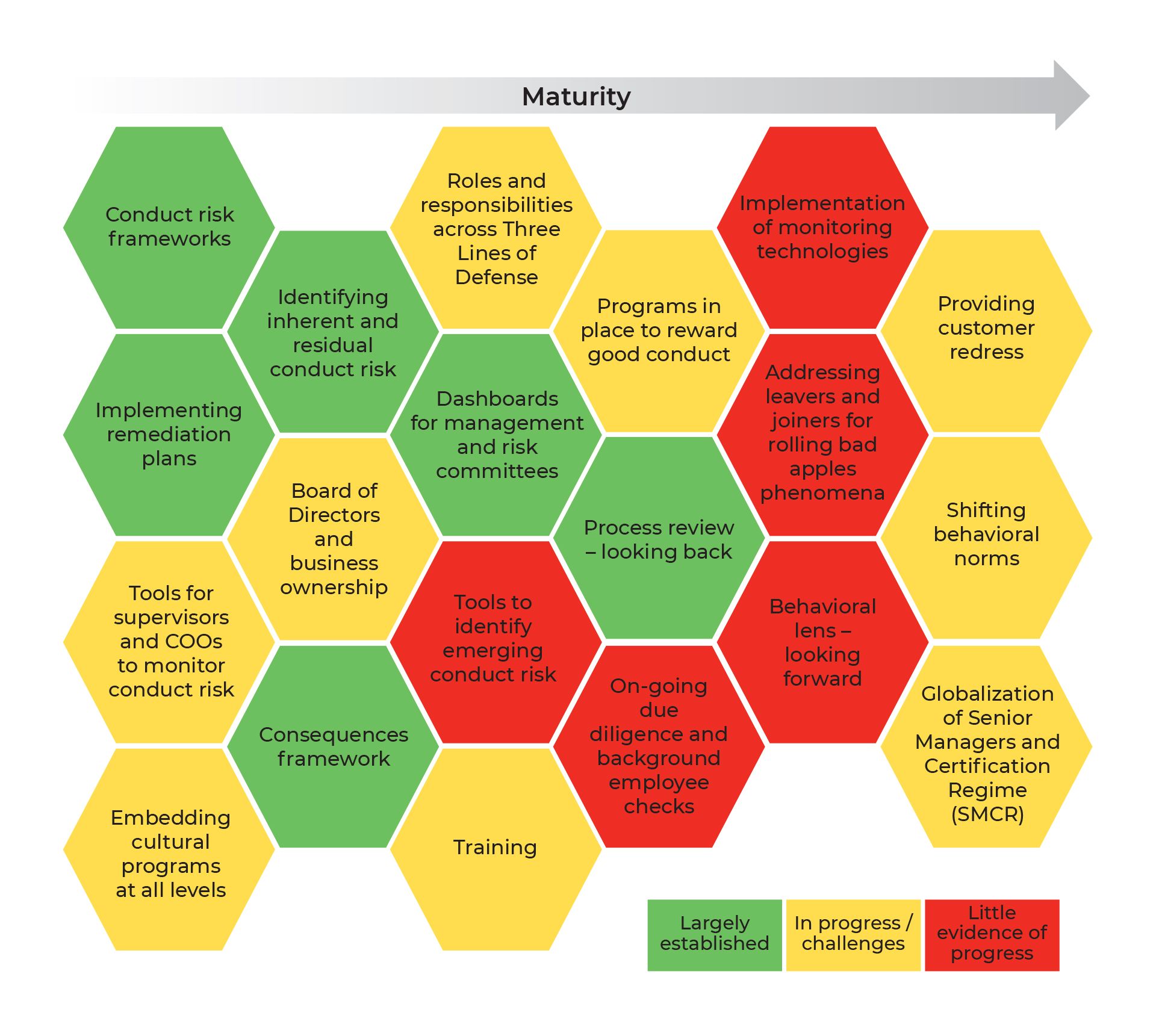

The table below captures the current state of conduct risk across the financial services industry, highlighting that there is much need for improvement.

Stepping Up to the Challenge of Conduct Risk Control

No one is suggesting that it will be easy to close the current gaps. For one thing, conduct risk has proven to be challenging to define. From the outset, many banks have had to revisit and agree on their definition of conduct risk with regulators such as the U.K.’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA).

Though many banks initially treated conduct risk as part of their operational risk framework, regulatory direction and specific instances of conduct failures indicate that this is an inadequate approach. (Banks may have taken this point of view due to limited resources or because they did not understand the true extent of their exposure.)

The pressure and focus on banks’ costs in today’s market mean that regulatory initiatives are often staffed by individuals who have other roles and responsibilities to perform. Often there is insufficient expertise and bandwidth to implement meaningful solutions that reduce the risk profile of the organization.

Even with a conduct risk program in place, some banks still focus too much on crystalized risk, such as avoiding fines and losses, instead of developing forward-looking risk indicators. Another core question to consider is: when does a product or behavior move from being acceptable to unacceptable?

The FCA has rightfully made clear its view that banks are generally good at fixing things that have gone wrong but relatively weak at preventing something from happening. They, and other regulators, are thus increasing their focus on emerging conduct risk, and would expect banks to do the same.

Understanding the Drivers of Conduct Risk is Key

Understanding and addressing the drivers of conduct risk are essential to improving standards of behavior. While the starting point will vary from bank to bank, there are three core areas at the base of conduct risk:

- Ingrained factors: These are characteristics inherent to financial markets and their participants, such as information irregularities between banks and their clients or clients’ relative lack of financial sophistication.

- Common practice: The financial services sector has long-established behaviors and conflicts of interests that could prevent markets from working as well as they should.

- Outside influence: Ineffectively responding to macroeconomic developments that impact financial markets and consumers can lead to poor conduct outcomes.

While measuring conduct risk can be challenging, it may be helpful to assess drivers through three lenses: specific business units, the overall bank, and the strategic medium- to long-term outlook.

Establishing a Solid Framework for Conduct Risk Management

Most businesses stress the importance of senior executives playing a role in conduct risk, particularly in raising the visibility of a program. Good corporate culture comes from the top and should be articulated through extensive internal communications programs. The most successful programs usually have regular board-level reviews that assess and, more importantly, challenge the plan.

Banks that implement strong conduct risk management are intrinsically better at identifying the drivers of conduct risk, such as conflicts of interest. The conduct risk program itself should be tailored to each bank’s needs based primarily on size, business model, and geographic reach. The framework should take into account both short- and long-term goals.

Banks need to establish conduct risk frameworks following a deliberate approach that applies expertise in regulatory compliance to an in-depth analysis of company data, bringing in outside advisors, as needed. Steps include:

- An analytical review of any current conduct risk frameworks.

- Analyzing company datasets to identify where risk management failures are most likely to appear.

- Reviewing conduct risk profiles and devising associated remediation plans.

- Implementing mechanisms to embed conduct and culture processes throughout the organization.

- Focusing on the design and operation of conduct risk management information, including individual-based scorecards to identify historical and emerging conduct risks.

- Developing and implementing a supervisory framework that supports global senior manager accountability regimes.

The Takeaway

Misconduct scandals occur in every industry, but in the financial sector, they have become too frequent. Businesses that fail to bring conduct risk in line face regulatory action, fines, and reputational damage, which can harm a company for years beyond the event. We have seen a significant financial impact on banks due to conduct-related regulatory action—and it can all stem from an individual’s actions. Instead, best practice and regulatory expectations call for identifying conduct risk before it emerges, with effective governance based on solid risk management frameworks.